Mini5 Word Crusher

Tags: computer nec cpm mini5 bungo pickups repair retrochallenge retrochallenge-october-2022 word-processor

Used Japanese word processors have been a tempting siren for me for years, but I’ve avoided them so far due to the huge shipping weight and my general illiteracy in the language. What if those word processors could run CP/M and had a CRT? Ah, now that’s a different story.

Japan’s computer industry produced a lot of dedicated word processors (“wapuro” is the fun-to-say portmanteau.) Most of them are just dedicated machines with huge ROMs sold at a cheap rate. Every major company seems to have put in a contender. Our friends at NEC were no exception.

Hacker History

I’d seen mini5HAs for sale before, but what really pushed me over the edge was learning that they represented an interesting part of Japanese doujin1-hardware/software history. A J-PC magazine called PC World (not to be confused with “our” PC World magazine) did a special series giving tips for their use as a general-purpose CP/M computer.

Naturally, as these “文豪” (bungo; “Literary Master”) machines were somewhat cheaper than a “real” PC at the time (¥100k or less compared to ¥400k or more for a V30-powered PC-9801, without a monitor) they became popular systems for broke college students to use in order to get on BBSes. And what do constantly-connected, broke college students have a lot of? Free time to port compilers and tools from other CP/M machines, namely the Amstrad PCWs. Even MS-DOS was ported through a combination of community-contributed patches.

Software wasn’t limited to just community/hacker stuff either, as it appears there were commercial releases of Tetris and Sokoban, among others, for the platform (as well as for other x86-adjacent word processors of the time, such as the Sharp, Toshiba, and Panasonic units.) This is the kind of surprisingly deep, obscure stuff that I love discovering about the highly diverse Japanese 80s/90s PC ecosystem.

Choosy Blogs Choose Bungo

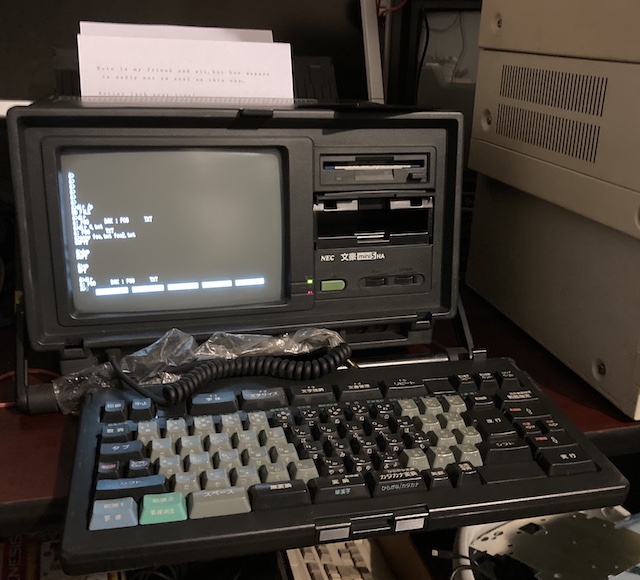

So which machine did I pick? This PWP-50HA NEC mini5HA. This is a portable, CRT-based word processor with a built-in printer.

At first, I thought that the entire mini5 series was Z80-based, but that only applies to earlier models. The particular model I’ve chosen is actually running an NEC V20. I assume (but have not confirmed, because I haven’t dumped the ROM) that CP/M-80 must run in the 8080 emulation mode of the V20.

If you’re interested in using a mini5 as a CP/M machine, you should know that there are lots of lighter LCD-based “portable” models such as the mini5 CARRY WORD. Those models will be both cheaper to ship, and probably easier to repair if anything goes wrong. I should have done more research first, but then I would have ended up with one of those instead of one of these.

As an aside, a surprising number of TV commercials have been dumped for the mini5/mini7 series, as well. Here’s some of my favourites:

- Famous novelist Shusaku Endō procrastinates with clip-art and special fonts, then escapes the building when nagged too many times by a subordinate;

- Some office workers bring a mini5RX to a baseball game and get clobbered;

- A picky boss is placated by a mini5SX’s print quality, to a catchy jingle

Arrival

Unsurprisingly, I was the only bidder on this heavy, obsolete niche machine at ¥1000, but the shipping (both domestic and international) cost a whole lot more.

Through the power of “paying too much for shipping,” I was able to get the wapuro to my home, even though Japan Post was temporarily not shipping to Canada. I better be on FedEx’s Christmas card list after this.

One side of the machine has this “memory card” slot. I’m assuming that this is meant to take PCMCIA-style memory cards, and imbue the Mini5 with new fonts, etc.

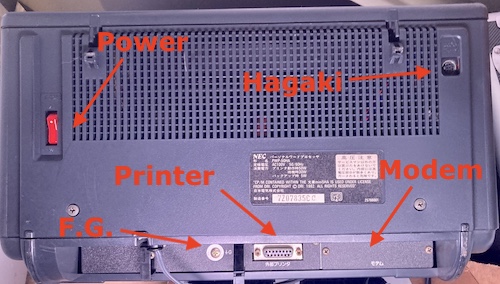

There are some interesting ports on the back of this computer/wapuro, including an external printer port, a “modem” slot (sadly unpopulated2,) and the hagaki feeder port. More on that last one in a bit, as it will take some explanation.

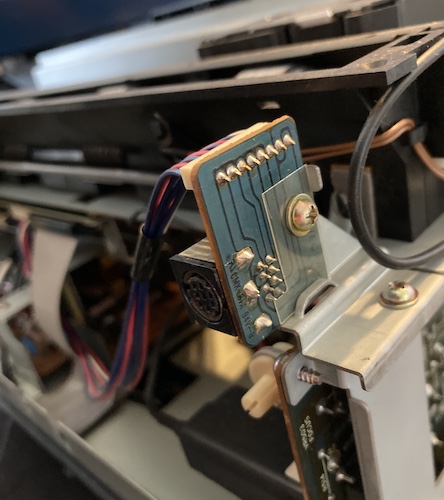

On the front of the system, there’s a 9-pin mini-DIN port that claims to be RS-232, though I don’t know the pinout. It’s definitely not the same as Mac serial, which is 8-pin. There is also an 8-pin mini-DIN port labelled “scanner,” obviously intended for a hand scanner, used to add graphics to a document.

As you can tell from the picture, the machine is equipped with a single 3.5” floppy drive. Generously, the seller included an unlabelled diskette with the system, likely forgotten by the previous owners inside the Osborne-esque disk storage drawer beneath the floppy drive. Finders keepers!

Unbusting the Plastics

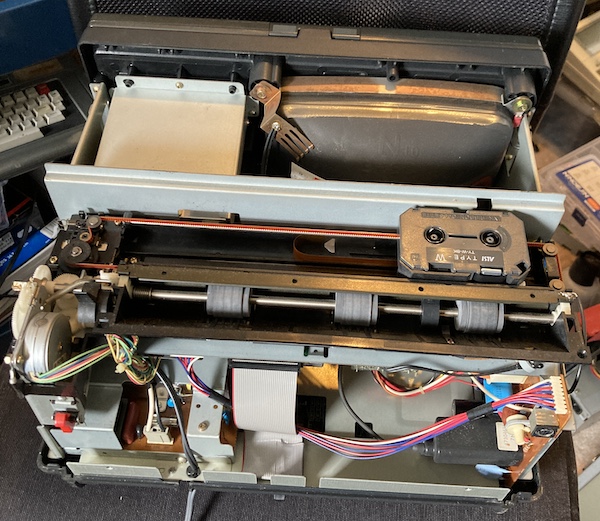

When the word processor arrived, despite the extra protective padding added by my proxy, a few of the screw holes in the plastic were busted out from the rough shipping via FedEx (Japan Post has never delivered to me a box this badly crushed.) Luckily, most of the plastic was still present and wrapped around the old screws like a washer, so I carefully removed everything and took a look inside.

The NEC-brand CRT monitor seemed to be in good shape, with the front mounts intact, the neck board firmly installed, and no sign of cracked solder joints on the flyback transformer. None of the boards seemed to have shifted out of their positions either, and “glass-like” components like fuses and diodes were not in little glittery fragments at the bottom of the case. Considering the shipping condition and the weight of the system, I think I got away lucky.

I mixed up some cheap two-part epoxy and went to town reinstalling and reinforcing these holes. Although I got the mix ratio a little wrong on the back hole, I was able to sand off the ‘sticky’ uncured resin with a little bit of 320 grit. Some small plastic ribs for case alignment have unfortunately gone missing as well, but it doesn’t affect the case when it’s installed.

The little flip-out feet on the keyboard are gone (with broken-off mounting pegs, to add insult to injury,) but it feels like that happened a long time before it was shipped. Also, the carrying handle/prop-stand was very difficult to move into and out of the “deployed” position, as the little metal cams inside the case don’t want to slide smoothly against the plastic.

The computer is in generally good condition, but there is rust over most of the screws, indicating it has been sitting in non-humidity-controlled storage for quite some time.

Hagaki

This mini-DIN port on the back of the machine is labeled “hagaki feeder,” which I had to research. A hagaki (はがき) is a Japanese postcard size (4x4 inches, narrower than the Western 4x6) and, from the name, I assume this feature is for driving some kind of “feeder” machine that loads a bunch of blank postcards on demand into the printer for a mail merge operation. No doubt meant for sending out holiday cards or snail-mail spamming.

Unsticking the Legs

Like I said a few paragraphs ago, the “prop” legs on either side of the machine, which double as a carrying handle for semi-portability, were stuck pretty tight. Although I could shift them with a lot of effort, all it took was a look on the inside to notice that the joint was rubbing metal on metal. I decided to dismantle the legs before reassembling the machine, in order to lubricate the joints.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t figure out how to take the legs all the way off of the machine. The furthest I got was removing the crossbar, which is just held on by two JIS screws under the rubber feet. Once that was removed, I was able to actuate the legs independently, hold them in place and douse the bearing and sliders with Fluid Film.

Once buttoned back up, things seemed to work a little smoother, though I still wouldn’t call it “easy” to move. No doubt it has spent nearly its entire life in one position on a desk. More work in the future to be done.

Another thing that needs repair is the manual paper-feed knob for the printer; this works like a typewriter and pulls the paper into the print area. Unfortunately, the plastic has aged out, turning an ugly chalky white-grey colour, and the “D” shaped moulding which turns the shaft inside the machine cracked right open. Some masking tape was holding it tight for awhile, but it’s definitely no longer doing that now. I think I’ll try epoxying this as well, but for now, the paper can be fed the old-school way.

Test Fire One

I reassembled the top case. It doesn’t fit quite straight, indicating that there may be more damage than I thought. However, it was tight enough that the guts weren’t exposed, so still fairly safe.

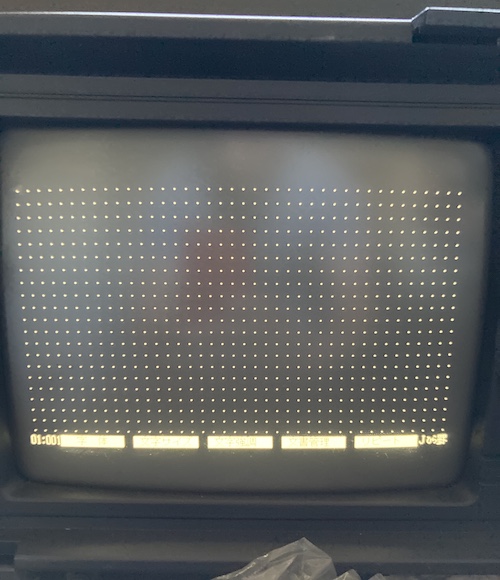

I plugged it into my 100V step-down transformer, and flipped the switch on the back. Nothing happened until I pushed the green button on the front, at which point an LED lit. And then, after a long delay as the tube warmed up, this:

![A warning dialogue is on screen. It reads basically: 100V AC has been cut off, so [the computer] will be reset to the initial state. Press the execute key.](/assets/pwp50-power-loss-warning.jpg)

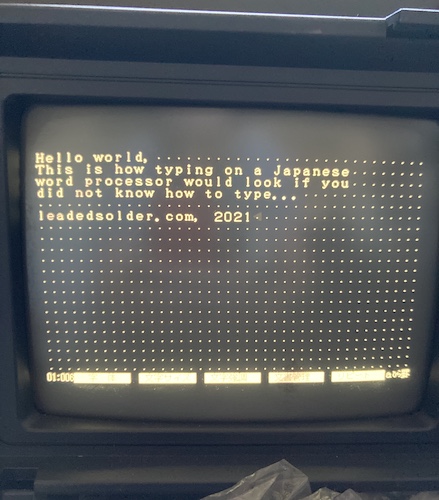

I fumbled around a little bit to find the “execute” key and found it on the very far right of the keyboard. Pushing it made the computer proceed through a CP/M boot screen and then drop me into the text editor:

After pushing the “character” lock button, I was able to type in English. The keyboard feel is hard to describe; it feels tactile, but with a lot of springiness.

It was a little hard to adjust to using the small space key on the middle-left of the keyboard, as even though I usually hit space with my thumb, I always want to hit the middle of the keyboard for it.

Wow. The screen is absolutely stunning on this computer, especially considering the low cost: the raster is razor-sharp, and it’s very easy to read even kanji characters. I was completely delighted with my purchase and even the huge shipping cost by this point. What a cool machine!

Pushing the green power button on the front immediately puts it into (hopefully) low-power sleep mode. It worked pretty reliably to come out of sleep, with my buffer right where I left it. This would be a very pleasant typing experience in the late 80s.

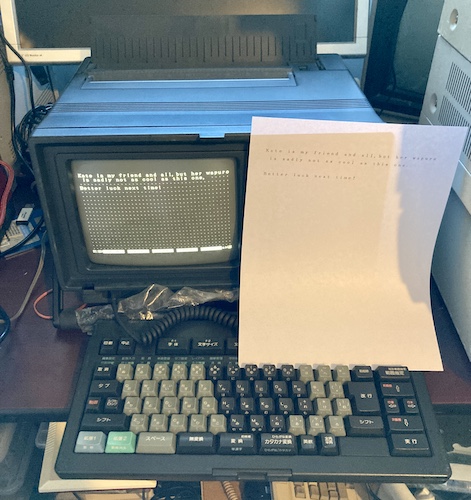

Did the printer work? I looked around the keyboard until I noticed that the very top left one, rather than being an escape key as you would expect, was actually a “print” key. I stuck some scrap paper into the loader, and after some fiddling with the lock-unlock switch around the drum, managed to feed it through by hand.

What better thing to print for my test run than to flex on a fellow old-computer nerd’s rival brand of word processor? Kate will understand.

Okay, let’s check out the disk that came with it. Maybe there is some top-secret information on there, or a treasure map to a working X68000.

Panic! At The Disko

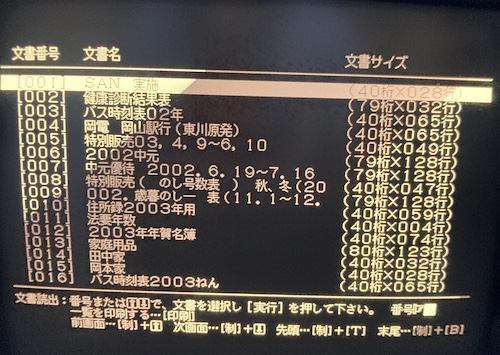

One of the F-keys on the keyboard, F4, was marked “file operations.” I whacked it, and then when another sub-screen came up asking me which file operation I wanted to perform, I panicked and hit it again3. This seemed to please the machine, and the floppy drive happily ground away until it popped up a file listing.

Although it’s difficult for me to follow without the help of Google Translate, I figured out that this machine had been used up until around 2007 for things like lists of people to send New Years cards to – hey, maybe they used the higaki feeder!

One of the last files listed appears to be a bus schedule explaining the times that buses would arrive and depart from “Higashikawa Nuclear Power Plant” (presumably a Google-translation error, and it meant the Higashidōri plant, which has not generated electricity since 2011, following the Fukushima disaster.)

I archived the disk before I started, by using a Greaseweazle. Although the disk would later prove very useful, it began to feel a little unseemly prying through memos about various office goings-on. The Bungo is also supposed to be equipped with a spreadsheet tool and graphic import tool (through a hand scanner,) but I couldn’t figure out how to get to those.

Okay, enough word processing. Now to make Gary Kildall proud with some CP/M!

Completely Pointless Machine

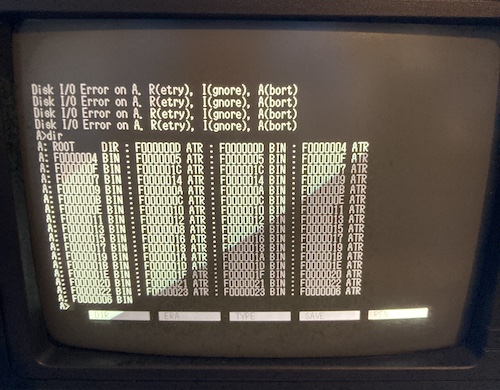

From reading on Japanese websites, I knew that holding Control (the red key) and Extended 1 (the blue key) during a boot would kick me into CP/M. It did indeed start CP/M 2.2, and then the empty floppy drive ran forever, searching for something to read.

If I had read a little closer, I would have also realized that I needed a formatted disk to boot CP/M. It’s a good thing I got a disk with the computer, because I wouldn’t want to have to figure out how to format a new one through the word processor interface.

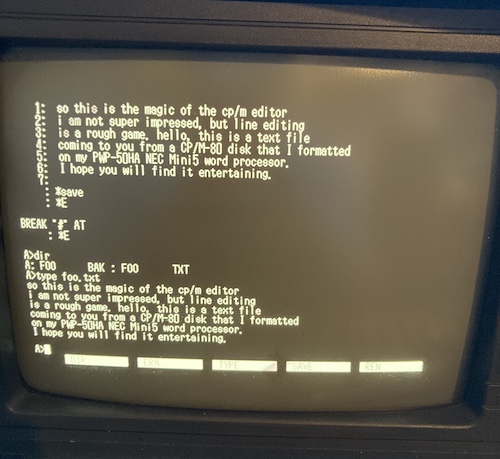

I popped the nuclear memo disk into the machine, and it stopped complaining and brought me to the A> prompt. As expected, the Bungo uses a CP/M-readable filesystem to store the word processor documents on its diskettes:

Presumably, the BIN file holds the actual character data, and ATR is some kind of metadata or “attributes” about the document, such as the title of it. I’ll play with those later, as I’m sure the Japanese internet has developed tons of tools to help rescue orphaned documents from these old machines and bring them into the modern era.

After booting, I was able to eject the boot disk, insert a double-sided blank disk, and format the new disk with format. Now I had a blank disk that I could boot into CP/M and play with to my heart’s content.

CP/M-80 starts up so quickly from a cold boot that the CRT hasn’t even fully warmed up by the time the command prompt is ready. There’s a bit of vertical hold jitter as it warms up, which perhaps suggests a dried-out cap somewhere in the analogue board, but the raster is still dimensionally correct and the funkiness goes away quickly.

Now, I’d barely used CP/M before this. The mini5HA is the first CP/M machine that I’ve owned4. I didn’t know all of the commands (e.g. ERA (erase) to remove files and PIP to copy files) and I had a hard time getting to grips with the built-in line editor ed until I read this exhaustive page about its function set.

I think I could eventually get used to this, but it feels like a waste to be using a line editor in an interactive session. Sadly, I wasn’t able to locate a port of vi or vim to this thing, but maybe one is out there!

So, that’s a very brief intro of the NEC mini5 line of word processors. What should I do with it next?

How about… Tetris?

Repair Summary

| Fault | Remedy | Caveats |

|---|---|---|

| Machine has the case broken off from shipping | Epoxy it as well as I can. | Feeder knob remains broken, although it was probably broken before. |

-

The Japanese word “doujin” has a lot of English interpretations, but we’ll use it in the spirit of “clique” (同人.) You can think of this as sort of a “hobbyist group” or loosely-affiliated club. In the modern era, a lot of English speakers will use it as a direct equivalent to a word like “homebrew” or “indie.” I’m not a Japanese scholar, so consult one before you use a word like this on the internet where everyone can read it. Oops. ↩

-

The modem option (PWP-50HA-MB1) was ¥20,000 new. NEC margins are notoriously brutal, even for supposedly “budget” computing appliances like these. ↩

-

The entire experience was eerily reminiscent of my attempts to order meals in Japan. Just keep saying hai (or in this case, execute) until something ends up on your plate that you can eat. ↩

-

Obviously, I have lots of Z80 machines that could run CP/M-80… but they haven’t. ↩